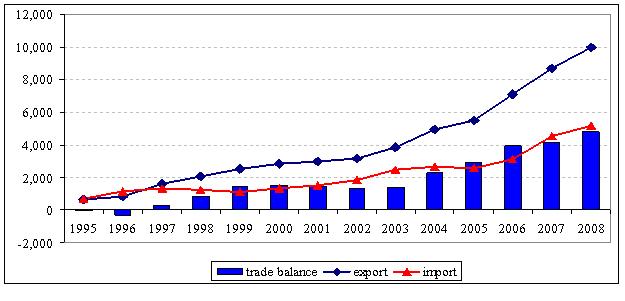

| Large potentials for expanding ASEAN-EU trade remain unexploited, and an ASEAN-EU Free Trade Agreement would benefit Vietnam, of which export has always been a key growth factor. But, moving toward free trade has never been purely beneficial, and engaging in FTAs presents enormous challenges to the country, which is developing rapidly but with high vulnerability to external shocks and low risk management capacity. The social and environmental impacts can also be detrimental.

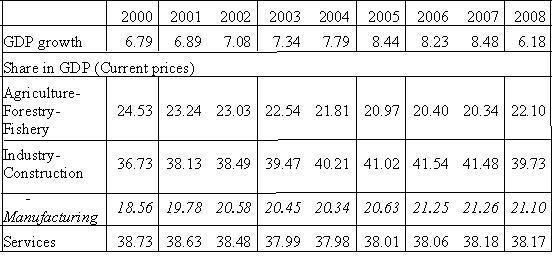

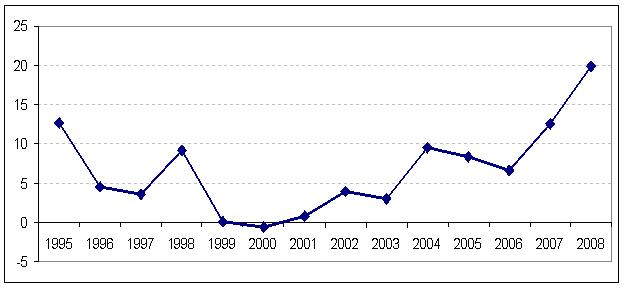

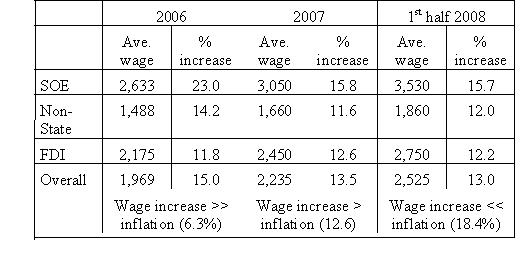

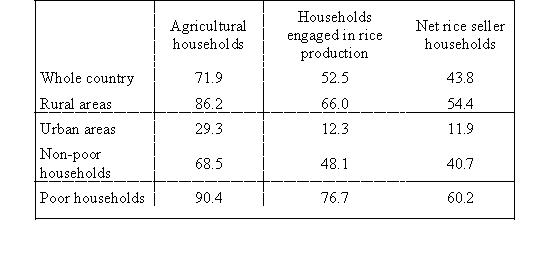

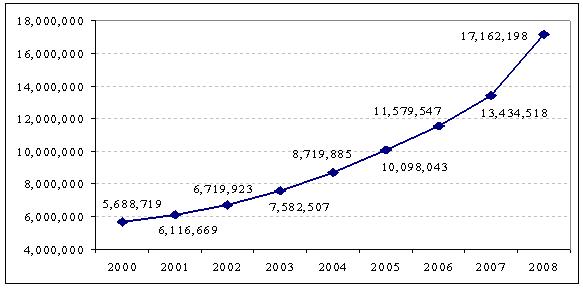

Box 1: Income improvement in Vietnam, 2000-08 There might, however, be some indirect impacts on the environment. As discussed above, a key challenge for Vietnam in implementing an EU-ASEAN FTA is that it will continue to exploit static comparative advantage in labor- and/or resource-intensive products, without realizing dynamic comparative advantage in those with high technological content. That is, engaging in the FTA may threaten Vietnam’s chance to develop and apply new technologies which are more friendly to the environment. In this respect, the FTA may be environmentally harmful to Vietnam. References |

Researchers weigh potential impacts of ASEAN-EU FTA on Vietnam

Source:vpdf.org.vn

Copy link

Print the article

Print the article